While the South China Sea captures headlines and the North Atlantic remains the bedrock of traditional alliances, the Indian Ocean has quietly emerged as the decisive arena for the 21st century. Hosting the world’s most critical trade veins and a growing matrix of great-power rivalries, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is no longer a mere “transit space” between East and West. It is the center of gravity where the future of global energy security, digital connectivity, and maritime order will be written.

The Connector, Not the Container

For centuries, the Indian Ocean was viewed through the lens of colonial “stations”—a series of ports connecting European metropoles to Asian markets. In the modern geopolitical imagination, it is often treated as a “container” through which goods pass on their way to somewhere else. This is a strategic error.

The Indian Ocean is the world’s ultimate connector. It is the only ocean named after a single country, yet it is arguably the most internationalized body of water on the planet. Covering roughly 20% of the Earth’s water surface, it links the oil-rich Middle East, the industrial powerhouses of East Asia, the emerging markets of Africa, and the strategic depths of Australia.

As of late 2025, the data is undeniable: over 60% of global maritime trade and 80% of the world’s seaborne oil trade transits these waters. If the Pacific is the theater of “grand strategy” and the Atlantic is the theater of “values,” the Indian Ocean is the theater of utility. It is where the global economy breathes.

The Triple Crown: A Geography of Fragility

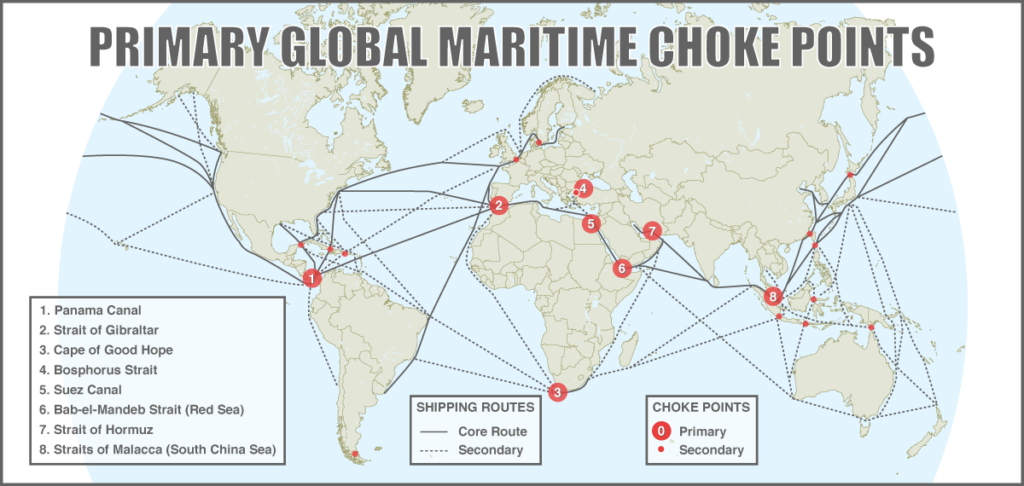

The strategic importance of the IOR is concentrated in three narrow gateways, known as the “Triple Crown” of choke points: the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, and the Strait of Malacca.

- The Strait of Hormuz: The world’s most important energy artery. Despite the global shift toward renewables, nearly one-fifth of global oil consumption passes through this 21-mile-wide gap daily.

- The Bab el-Mandeb: The gateway to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. The 2024–2025 Red Sea crisis, driven by Houthi insurgent attacks on commercial shipping, served as a brutal reminder of this point’s fragility. At its peak in early 2024, container throughput in the Suez Canal dropped by over 50%, forcing vessels to take the 4,000-mile detour around the Cape of Good Hope.

- The Strait of Malacca: The primary link between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. For China, this represents the “Malacca Dilemma”—a realization that its energy security is dependent on a narrow waterway that could be easily blockaded by a superior naval power.

This “Geography of Fragility” means that a localized conflict in Yemen or a skirmish in the Persian Gulf does not stay local. It propagates instantly, manifesting as inflation in Europe, fuel shortages in India, or manufacturing delays in Japan.

The Artery of the Asian Century

The shift of global economic power toward Asia has transformed the Indian Ocean into the primary energy artery of the world. While Western nations debate the pace of the energy transition, the “Asian Century” remains powered by fossil fuels that must transit the IOR.

For China, Japan, and South Korea, the Indian Ocean is an existential lifeline. Approximately 80% of China’s oil imports and 90% of Japan’s pass through the IOR. This dependency has fueled a massive naval expansion, most notably China’s “String of Pearls” strategy—a network of commercial and military facilities stretching from the Port of Djibouti to Gwadar in Pakistan and Ream in Cambodia.

However, the artery is not just carrying oil. In 2025, the Indian Ocean has become the nervous system of the global internet. Undersea fiber-optic cables, which carry over 99% of international data, are increasingly concentrated in the IOR. Major projects like the 2Africa Pearls cable, set to be fully operational by the end of 2025, connect 33 countries across Africa, Asia, and Europe. These subsea “pipelines” are the new frontier of strategic competition, with the US, Japan, and Australia (the Quad) racing to provide “trusted” cable infrastructure to counter Chinese digital influence.

The Great Power Matrix: A New Chessboard

In the 20th century, the Indian Ocean was a “British Lake” and then a theater of Cold War maneuvering between the US and the USSR. Today, the matrix is far more complex, defined by a triangular competition between India, China, and the United States, with middle powers like France, Turkey, and the UAE playing increasingly assertive roles.

1. India: The Preferred Security Partner

Under its MAHASAGAR (Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth Across Regions) doctrine launched in 2025, India has moved beyond its traditional role as a “Net Security Provider” to becoming a “Preferred Security Partner.” New Delhi views the IOR as its primary sphere of influence. With two operational aircraft carriers and a third on the horizon, the Indian Navy is positioning itself as the guardian of the central IOR. Its strategy focuses on “Maritime Domain Awareness” (MDA)—using a network of coastal radars and satellite data to track every vessel from the Mozambique Channel to the Andaman Sea.

2. China: The Global Maritime Actor

China’s presence in the IOR has evolved from “anti-piracy task forces” to a permanent military footprint. The commissioning of the Fujian, China’s first supercarrier equipped with electromagnetic catapults, in 2025 marks a turning point. Beijing’s goal is no longer just protecting trade; it is about projecting power far from its shores. By securing access to deep-water ports like Hambantota (Sri Lanka) and potentially naval bases in East Africa, China is effectively “short-circuiting” the Malacca Dilemma.

3. The United States: The Offshore Balancer

The US remains the preeminent naval power in the region, centered on the base at Diego Garcia. However, Washington’s focus is increasingly “Indo-Pacific,” a term that often prioritizes the Pacific. In response to China’s rise, the US has pivoted toward empowering local partners. The “Integrated Undersea Surveillance System” (IUSS) and increased cooperation with the Indian Navy are part of a strategy to maintain a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” without needing a massive, permanent fleet presence in every corner of the ocean.

The Governance Paradox: A NATO-less Ocean

Despite its existential importance, the Indian Ocean remains the most under-governed region in the world. There is no “NATO of the Indian Ocean,” nor is there a comprehensive security architecture like the OSCE in Europe.

The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) are the primary multilateral forums, but they are often hamstrung by the “Governance Paradox”: the very diversity that makes the IOR important makes it nearly impossible to govern. The interests of a landlocked African state, a wealthy Gulf monarchy, and a Southeast Asian tiger are rarely aligned.

In the absence of a “Grand Alliance,” we are seeing the rise of mini-lateralism. The Colombo Security Conclave (CSC)—comprising India, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, and Bangladesh—is a prime example. These small, issue-based groupings are more agile and effective at tackling non-traditional threats like illegal fishing, human trafficking, and maritime disasters than larger, more bureaucratic organizations.

The Pre-War Arena: Conflict Without Combat

As we look toward 2030, the Indian Ocean is best described as a “pre-war arena.” It is not yet a battlefield of kinetic conflict (with the exception of the Red Sea disruptions), but the chessboard is being set.

The competition is currently playing out through:

- Infrastructure Diplomacy: “Debt-trap” concerns versus “High-quality” infrastructure alternatives.

- Fisheries Geopolitics: The use of “fishing militias” to assert maritime claims.

- Hydrographic Surveys: Mapping the seabed for submarine “silent highways.”

If a conflict were to break out in the South China Sea or over Taiwan, the Indian Ocean would be the “second front.” The ability to cut off an adversary’s energy supply at the Strait of Malacca or the Bab el-Mandeb would be as decisive as any missile strike.

Conclusion: The Future is Blue

The Indian Ocean’s status as a “quiet” center of gravity is changing. As the world’s most populous nations—India, Indonesia, and the collective states of East Africa—rise, the center of global consumption is shifting toward these shores.

The challenge for the coming decade will be managing the “Blue Economy” (sustainable maritime resources) while preventing the militarization of the commons. For the littoral states, the goal is to ensure the Indian Ocean remains a bridge between civilizations, not a barrier defined by the rivalries of distant capitals. The world’s quiet center is finding its voice, and it is the voice of a region that knows it holds the keys to global stability.

Pingback: Who Cares About the Indian Ocean? Interests and Rivalries

Pingback: How Indian Ocean History Shapes Modern Geopolitics

Pingback: Why the World Is Focused on the Indian Ocean in 2026

Pingback: Indian Ocean Chokepoints Explained: Seven Passages That Matter